At first I averted my eyes. With more decades than I care to think about in the graphic arts behind me I knew what was coming. I didn’t want to be one of those people. The disgruntled types I’ve spun by in the revolving door, leaving the graphic design world as I entered it.

I ignored the sinking feeling in my stomach as ineffable visions of ridiculous and horrifying things filled my feed. Non-artists were making convincing looking digital paintings for fun. I experienced a deep, instinctive revulsion to these images. The earliest outputs were horrific, with human eyes peering from every shadow, and an uncanny valley quality still clings to much of this work. Still, the speed and ease of producing these images bothered me. They could end up changing the way I do business.

If I still have a business, I mean, in a year or two.

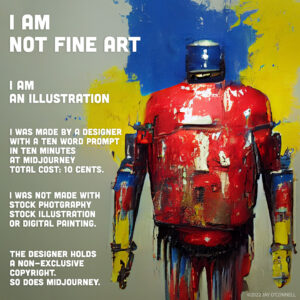

As these images flood social media, questions arise, and arguments ensue. Is this stuff Art with a capital A? If so, who is the artist? Is using AI art commercially legal? Assuming it’s legal, is it ethical? And most importantly to me and mine, will this put visual communicators like myself out of business?

First we must dispel some semantic based misconceptions .The software isn’t the artist (or illustrator.) It isn’t conscious. Really. It isn’t.

Stop thinking about this kind of AI as general human intelligence like the HAL 9000. Instead imagine the neural nets used by researchers to identify skin cancer from photographs. Developers of this software use large datasets of images of skin abnormalities, to train the network to diagnose cancer using algorithms that can see the difference between a non-cancerous discoloration and a dangerous melanoma.

Alarmingly, this skin cancer detecting software is already about as good as the average human MD.

The GAN at the core of AI art, the Generational Adversarial Network, works in a different fashion, but along similar lines. The G is a Generator that makes something, an image of some object (or tagged image that isn’t an object, but let’s start with something simple), say a flower. The A is the Adversary, trained to discriminate the Generator’s fake flowers from real flower images. The discriminator weighs in on the generator’s work, bouncing it when it fails its flower test. This process is repeated, iterated, in that way that computers do—very very quickly, and very very thoroughly.

So. Rather than the Hal 9000 painting to express its trauma at the necessity of murdering the fallible crew of the Discovery One, imagine an ordinary person typing the word ‘flower’ in a command line and highly specialized software spitting out a picture of a flower, boiled out of images of thousands of flowers.

At this point, the process feels something like illustration, or graphic design, where a client asks for something, and the craftsperson, the technician, or the factory, produces it. Even the GAN, the generational adversarial network, doesn’t smell like art. The discriminator, the adversary, is a picky client forcing the generator back to the drawing board a million times in a row, depending on the time budget. (Let me tell you, the Generator in this scenario does not feel like an artist in the slightest.)

So who or what exactly, is the artist here? The person typing the prompt feels sort of trivial. The developers training the generator and the discriminator feel more like creators, but this gets trickier quickly with multiple word and non-visual prompts.

The prompter, who we could now call an art director, (the person who commissions an illustrator) requests “a daisy that looks like a bulldog.” So the generator goes looking at its image data set for daisies, bulldogs, photos or paintings, and presumably pictures of daisy-bulldogs, if they exist, or dog-flowers more generally. The generator starts synthesizing images, and the discriminator shoots them down ruthlessly, until the discriminator sees something it thinks isn’t a fake-bulldog daisy. Or rather, an image balancing the prompts to answer two questions from the difficult client at the same time. Now the prompt writer starts adding weight-codes to the different words, and you can see our robot visual toy becoming a tool in the human hands of a skilled operator.

Create any prompt you want, a dozen things fused into an image. You don’t have to sketch it first. It doesn’t matter if you can visualize it or not, not your job, you’ll know when you don’t like it. And you’ll bounce it. Let’s call you a Creative Director. The discriminator now is the poor art director you are bossing around, and the generator is the individual contributor in this equation. Visualize the illustrator as a woman sharing her screen in a zoom conference, audio muted, holding her head in her hands moaning softly as her boss and her boss’s boss explain how everything in the image must be made bigger. Most of what she gets badgered into making are clichés designed to emulate a comparable image that has succeeded in the marketplace.

It all feels very commercial. Once artists start training their own discriminators, feeding it their proprietary output, the ‘is it art’ question goes away; The program becomes analogous to whatever human brain regions make art; the GAN becomes a kind of prosthetic. A tiny handful of these kinds of artist programmers have popped up in the fine art world over the last ten years.

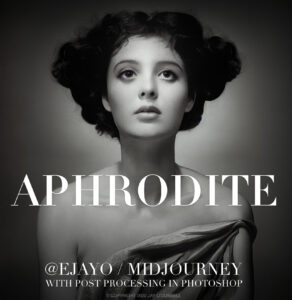

But at the present a lot of AI art looks like what it has been trained to be by its users, the grandchild of mall gift shop velvet black light posters, knock offs of Frank Frazetta paintings, or visual jokes that lean on art art history, because one of the things that the discriminator can discriminate is an artistic style. (Wanna see a spaceship designed by Mondrian? Type that in. I have.)

Suddenly, the AI is creating something that we used to call a (copyrightable) derivative work, when humans did it.

Now, throw in the intangible word prompts, which aren’t mysterious, the GAN isn’t conscious, but it is trained with human authored tags, labels that encode human value judgements about images. Human cultural bias. Oh, and of course racism, the datasets here represent the work of thousands after all. One training set image included a photo of a dark-skinned, middle-eastern type man and the tag, ‘terrorist,’ for example.

Mixing the tension between multiple word prompts, and the human value judgments built into the weighting and tagging of images, and the prompt writer’s judgements about what images they wish to cull or share, curate, publish or modify, and you end up with…

I’d call it Art (when it works for me) but I don’t have a lot of skin in that game. I’m a photobashing illustrator / designer, craftsmen for hire. To many fine artists this is all marketing material, like stock photography, an idiot factory pumping out interpolated and redundant visual clichés.

In any case, these images are made with blinding speed, exhibiting synthetic mastery of traditional mediums (paint, photography, ink, woodcut, whatever) that takes years of human effort to acquire. If this software is determined to be legal in any capacity it will transform the graphic arts industry significantly—without any instantaneous artist slaughtering apocalypse.

What comes next? As someone who has embraced new technologies while working in graphic design and related fields for thirty years, I have some ideas. But remember, I’m not a lawyer, and nothing in this piece should be constituted as legal advice.

I graduated from Syracuse University’s prestigious VISCOM program in 1990 with a degree in commercial art. According to my illustration professors most of us would never work in the profession. Then as now there were four times more designers than illustrators. My classmates and I would start out doing paste-up, and grow into designers as a kind of consolation prize.

Designers working by themselves create the bulk of visual communications we consume, and they do it on the cheap, without illustrators or concept artists. They use buck-an-image royalty free stock photography / illustration, photobashing, image editing, montage, and typography. Think Scarlet O’Hara in Gone with the Wind, making a dress out of the drapes to conceal her poverty. From a business perspective an illustrator is a necessary evil, too specialized to have on staff, and expensive to work with as a freelancer.

This makes them ripe for replacement. We’re going to end up with fewer people calling themselves illustrators and concept artists, and more people calling themselves designers and production artists. And at the top, a new kind of concept artist. Call them synthesists.

Because in the hands of a talented art director, and or a skilled designer or production artist, AI art platforms create professional quality commercial art at every level. I know because I’ve been making usable images for brave clients for the last six weeks. Generating, curating, and photobashing them into something… well, it’s the best work I’ve made in my life.

The changes in graphic arts in my lifetime have been breathtaking. When I started working production artists made mechanicals by gluing design assets onto stiff pieces of illustration board. You handed typewritten pages, marked up with red ballpoint pen, to a compugraphic operator who keyed in the text and output galleys on a slick, indestructible resin coated paper. Press type was used for headlines. You rubbed the letters down one at a time. There were optical stat cameras, for halftoning and resizing images, strippers who turned mechanicals into offset plates. Baths of chemicals in glowing red rooms, hissing airbrushes, people hunched over drawing boards with t-square and paste pots full of one-coat rubber cement.

All these specific jobs and skills sputtered away, production transformed, melted by desktop computers, laser printers, and digital imagesetters. Temps replaced production artists. Anyone who claimed to know desktop software got work. I sure did. Employers conflated knowing software with knowing paste-up and design. Paste up artists had to retrain, or quit the field.

But relevant to the challenge of AI art, all of this technology never really shrank graphic design broadly as a profession. It mostly changed job titles and swapped people around between various employers.

The amount of designed material increased hugely with the new tech, and the average quality of that content has been elevated as mimeographed typewritten office communications became fancy typeset documents, reports, sales and marketing materials, and websites.

The joke for decades being the ‘paperless office’ generating more paper than ever before.

But what about copyright?

A recent US patent office ruling held that a specific piece of AI art could not be copyrighted, that it was public domain as no human hand was involved in creating the end product. The judge somehow failed to note the human hands typing the text prompts. If this were to be the final world, AI art would be tremendous, replacing a huge amount of stock photography and illustration as we know it today.

But I don’t think all AI art is going to end up in the public domain.

Visual intellectual property is most vigorously protected at big companies at the level of a specific work. The movie. The cover. The software. The novel. The visual brands around these things, logos and trademarks and costumes. You can copyright Superman, but not every combination of words meaning super and man. You can’t copyright the idea of the superhero either. In short, you can copyright works, but not styles of content.

And AI art can emulate any style with which it is fed.

And copyright explicitly protects these kinds of derivative works. Superman is Moses, right? But he’s not a public domain character. A couple of Jewish guys in NYC in during the 1930s dreamed up a being who could punch the hell out of the nazis, informed by myth, and faith, and the colorful wrestling costumes of the era. Superman was synthesized, a creative amalgam.

Art styles have never been protected by copyright. Picasso didn’t copyright cubism. Dali didn’t copyright surrealism, or Dada. Jackson Pollock didn’t copyright abstract expressionism. Nobody ever got sued for painting like Rembrandt, or Normal Rockwell for that matter. For the last century illustrators have developed visual styles, often appropriating fine art styles and movements. When an illustrator’s style becomes popular, other illustrators copy it. Businesses don’t care about an artist’s signature. Business cares about products, not artisanal processes. You can page through the illustrator annual award collections, books and websites and observe that not only is imitation the sincerest form of flattery, it’s a good way to make a living.

The illustrator’s craft has always been produced as quickly and cheaply as possible. Oil paints can take days to dry. Acrylic paint dries in minutes. You can take a photograph faster than making an engraving, and faster than a painting. Before Photoshop, you would plunk a reference photo (perhaps culled from a magazine) on a light table and trace an image faster than drawing from life. All of these tools and practices nudge commercial art away from Art with a capital A, jettisoning process to get a faster product.

AI art does all this in spades. It cranks out stylistic copies, but like the human copycats, what it makes aren’t perfect replacements. It can’t infringe copyright, at least, not in any way the law really understands. The AI is informed by the visual tradition it has observed… swallowed…abstracted. But it doesn’t perfectly replicate specific works. It’s doing what human artists do, and in the process, it inserts enough noise, enough change, to make its fake Mondrians, its Pollocks, its Norman Rockwells easy to spot.

We didn’t ban the camera to protect the painter, the offset plate to protect the engraver, the desktop computer to protect the compugraphic operator, the scanner to protect the stat camera, the airbrush to protect the traditional brush, or digital painting to protect oils and acrylics and watercolors. I don’t see us banning this technology either.

But someday soon we may need to seriously rethink how job markets work. The speed with which this tech has appeared, and the rate at which it’s advancing suggests that the past may not make the best map for our future.

Optimists believe in a future where talented and trained people employ ever more intelligent tools to create more and better content, for a more visually sophisticated audience. Driven by AI that allows everyone to understand art at a deeper level–by being able to generate it, the way a MIDI sequencer lets a non-musician type out music.

Pessimists see new technology as an inevitable agent of inequality, a kind of a gun, used to rob creatives of the fruits of their painstakingly acquired skills.

I think the truth will be somewhere in between.

Regardless, AI art is here to stay.