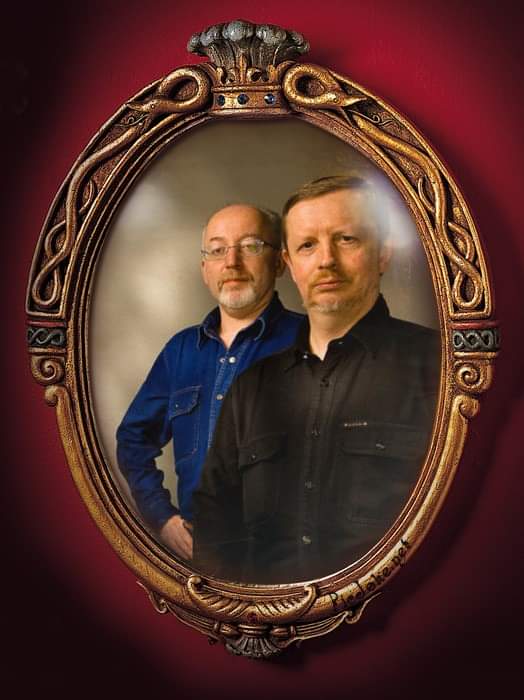

“Here we have a painting by an unknown artist, created in the early months of the large-scale war. Note how its realism, painstaking detail, and contrast achieved through the interplay of lighting, matches the symbolic message of the piece—”

He stood back and waited for the tour guide to usher her group along. After that, he’d get the chance to stand in front of the unobstructed painting, in quiet solitude, along with his thoughts and memories.

“Excuse me, is this the original?”

“There’s never been a physical original. This is a digital painting, created on a computer. You’re looking at a high-resolution print.”

“You said the artist is unknown?”

“He or she might have perished during the Russian invasion …”

If only the guide knew how close she was to the truth!

“Can’t the artist be identified based on their style? According to some characteristic features of their work?”

“A comparative analysis of the painting was conducted, both by the experts and using computer programs. Nevertheless …”

The familiar questions; the hackneyed answers. He could’ve easily enlightened both the tour guide and her group. Could’ve told them …

But what was the point?

Access to an open source neural network was like a holiday in its own right. Funny enough, FutureWorld had released the source code for their neuronet exactly on Lesha’s birthday.

Lesha had fully appreciated this unexpected gift. Alas, his responsibilities as the birthday boy had remained in effect. He’d test-flown the drone he was gifted to the approving cheers of the guests, uploaded the video clips it had shot to the net, and dragged everyone to the dinner table. He’d listened to the toasts given in his honor and cracked jokes. He’d DJ’ed an improvised dance party, and almost brought the house down with his sick beats. But he couldn’t wait for the party to end so he could have some alone time with his favorite desktop computer.

All that champagne tickled his mind with happy little bubbles, and nudged him toward adventure. Should he dig through the code and add something cheeky? A nice thought, but it wasn’t enough. He wanted more.

But what?

The code had been released, but they wouldn’t let him mess with the base functions and settings. No one was crazy enough to let him into the kernel. But what if he could copy the kernel onto a separate server and play around without all the restrictions? The firewall was preventing him from doing that.

Okay, but what if he tried it this way?

He woke up in the afternoon. His head was buzzing like a high-voltage transformer and he had a hard time focusing his gaze, but overall it wasn’t so bad. Lesha brewed strong coffee, fried up some bacon and eggs. He got back onto the computer while gulping down the rest of his meal and burning his throat.

Ohhh, what do we have here?

There was the kernel—a copy—hanging out on a remote server. How did he even get past the firewall the other night? Okay. What did he need to get done? Finish building two websites, set up a targeted marketing campaign for Relax, Inc. … He wasn’t behind on any jobs. All right, he was going to take the day off!

Lesha sang a little tune off-key as he began studying the kernel.

The new toy took up all of his free time. He even rearranged his daily routine around it. He worked on the paid projects before lunch; a few hours after lunch when the deadlines loomed, then spent evenings and late into the night in a vigil over the copied kernel, which Lesha had surreptitiously plugged into the FutureWorld network in parallel with the original.

The neuronet showed enormous potential. There were ample approaches for tuning and machine learning, enough for endless experimentation. With access to the kernel it was possible to dig deep into the settings, configure and modify feedback loops, launch intensive unsupervised learning routines using the convolutional auto-encoder—sparse coding for the win!

The original FutureWorld neuronet was built with a focus on recognizing photographs and drawings. It generated compiled illustrations based on user requests. Using the original neuronet’s knowledge base and his own settings, along with an experimental training program, Lesha got his progeny to produce requested illustrations faster and better. But that wasn’t enough for him; Lesha sought out neuronets that generated music and text, connected to them, and set out to enthusiastically expand the capabilities of his system.

Lesha’s kernel learned the additional skills in the next two months.

The next step was to teach the system to recognize the type of a given problem. This turned out to be easier than he’d anticipated. Images, music, text …. What else? Data collection, analysis, synthesis—those processes are universal. They can be applied to anything.

What if …?

You’re mad, he thought to himself. You’re mad, and you like it.

He plugged in a new training program: the deep Boltzmann machine with a probabilistic mathematical apparatus.

It was time to input data. Something simple to start with, something where the outcome was easy to verify. Weather forecasts? He uploaded statistics for the past ten years. Here you go, friend, study up, analyze, build patterns! He loaded fresh data from satellites and meteorological stations, the map of atmospheric fronts, cyclones, and anti-cyclones.

Time to generate a response: 7 hours, 13 minutes, 47 seconds.

“You’re lagging, friend. Fine, crunch those numbers while I get some sleep.”

Lesha rushed to the computer as soon as he opened his eyes in the morning. The monitor displayed a line containing ten snowflakes, three raindrops, and one mocking smiley emoji.

It was a serene September morning outside. Through the window he saw a sleepy sun lazily climb toward the horizon, preparing for a long ascent across the sky.

The thermometer read 17 degrees Celsius.

“Smileys, huh? Snowflakes?”

He’d long since been talking to the neuronet as if it were a living being. He figured he should name it. Nostradamus? That was foolishly melodramatic. What other soothsayers were there? “Albert Robida, a science fiction writer, artist, and futurist. Born in the South of France in 1848 …”

“Robida? That’s not bad. Sounds like a ‘robot.’ You’re going to be Robida, got it? Robbie, for short. Don’t let your namesake down, now!”

He introduced additional association routines, added patch-based training in parallel with the existing ones. He corrected parameters and adjusted tasks. A helping of free will wouldn’t hurt. Let Robbie switch between training programs on his own, or use all of them at once. Autodetection.

The cherry on top was the voice interface. “Okay Google” has got nothing on us!

Three months later, Robbie issued his first correct forecast. Then another one. After that, he predicted July heat and a thunderstorm on New Year’s.

“Are you messing with me?”

Robbie was silent.

Lesha recalled something he read online: “I’m not scared of a computer passing the Turing test. I’m terrified of one that intentionally fails it.” He’d been reading too much science fiction. A weather forecast was no Turing test, and Robbie was no artificial general intelligence, but merely a neuronet. Two correct forecasts, and then an error.

A normal result.

He’d been suffering from insomnia lately. He got up at the slightest noise, wandered into the kitchen, greedily drank water. He woke up irritated, frowned at himself in the mirror: a grim guy with a crumpled face. He kept meaning to shave, and kept putting it off.

The Robbie project wasn’t going well. The weather forecasts hit the bullseye nine times out of ten, but any attempt at a more complicated prediction bricked the whole system. Robbie would either not answer at all, or generated a mishmash of numbers, letters, and symbols. Lesha’s paying projects were overdue, he was perpetually behind and everything he tried to work on kept falling apart.

He woke up again. A strained hum emanated from the next room. The computer whirred frantically. The light from the monitor reflected in the frosted glass of the door, conjuring unpleasant associations with flashing police cars.

What’s happening?

The computer was in overdrive. A brew of acid tones boiled on the monitor. LEDs on the router blinked with machine-gun frequency. The neuronet was processing a colossal amount of information. The computer wasn’t reacting to input from the keyboard or mouse.

“Is that you, Robbie? What are you up to?”

No, that won’t do. Robbie won’t understand that.

“Robbie, stop. Cancel the problem.”

He belatedly recalled that Robbie was located on a remote server, with neural processors spread across the entire world. So, what was happening to his computer?

A line of text appeared on the monitor above the acid brew.

The solution in 17 … 16 … 15 …

“The solution to what?”

3 … 2 … 1 … 0.

The brew froze in place. The text blinked and disappeared. Colored rectangles broke into pixels which organized themselves into a picture like a jigsaw puzzle. Lesha was staring at the image when something heavy and loud boomed outside.

The windows rattled in desperation. The lights and the monitor went out. The date remained imprinted on Lesha’s retinas, as though engraved by a laser.

February 24, 2022.

That’s how the war started for Lesha.

The war had actually been going on for a long time, but it was somewhere far away, a familiar, disturbing background noise. But everything changed that day. One of the first rocket strikes demolished the data center where Robbie’s kernel was stored. Lesha was luckier; his neighborhood merely lost electricity.

He wandered aimlessly in his apartment. He phoned someone. He went somewhere. To buy groceries, perhaps? He waited in lines, returned home. The power was restored. Cable internet still wasn’t working, the data center was unreachable. Lesha learned about the strike from a Telegram channel. Thankfully, there had been no one at the data center at four in the morning. That is, there were no people.

There was only Robbie. And now he was gone.

The painting Lesha had seen on his monitor before the strike was saved to his solid state drive by some miracle. He studied it for a long time. He took care of his daily chores, kept coming back to the computer and digging through the files which Robbie had loaded right before the end; he kept opening the painting.

On the tenth day he received his draft notice.

“You work in IT?”

“Yes.”

“Have you served in the army? Do you have any military specialization?”

“No.”

“Then what the hell are you doing here?”

“I was sent a draft notice! And I already passed my medical examination.”

“I see …”

The enlistment officer leafed through Lesha’s papers. “What am I supposed to do with you?”

“An IT guy, you say?” A man in his mid-forties stood in the door. He wore a faded camouflage uniform; his gray hair was buzzed short, his cheekbones high. His piercing eyes studied Lesha from under sparse, bleached eyebrows.

Lesha nodded.

“What’s your skillset?”

“Websites, databases. Neural networks, digital ad campaigns …”

The gray-haired man appeared unimpressed. “What else?”

“I can fly a drone!” Lesha blurted out.

“Where am I supposed to get you a drone?”

“I have my own!”

“Which one?”

“A Mavic 3.”

“And you’re sure you can pilot it?”

“I’m positive.”

“Can you teach others to do it?”

“No problem.”

“What’s your name?”

“Alexei Nechiporyk,” said Lesha.

“I’m Captain Zasyadko.” He turned to the recruitment officer. “Grigorych, sign him up for my company, as a drone operator.” Then, back to Lesha: “Is a day enough for you to get ready? The day after tomorrow, be here at 9 a.m. with your things. Grigorych will tell you what to pack. And don’t forget the Mavic!”

That’s how Lesha joined the army.

Basic training was both simple and complicated. Lesha loved operating the Mavic and teaching others to do so. He had no trouble assembling and disassembling an automatic rifle. He quickly learned to shoot, and even enjoyed target practice. Learning First Aid was fine. Digging ditches wasn’t so great.

The worst were the physical training and discipline. Lesha could barely make it a full kilometer in full gear. Two weeks later, he could manage two kilometers. Then three …

And then the training ended.

“Mavic, this is Artist. Confirm?”

“Artist, this is Mavic. I hear you.”

“Is the birdie ready?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Launch.”

“Birdie is away. Sending video.”

“I have visual.”

“I’ve got two APCs, one armored carrier, one tank, and an anti-tank grenade launcher. Painting targets.”

The aging tablet’s firmware had been patched and upgraded by Lesha—junior sergeant Alexei Nechiporyk, codename Mavic. With a flick of a finger he marked targets on the tablet; coordinates and images were automatically sent to the gunners.

“Data received. Working.”

“I’ll keep the birdie up in the air for now. If they try to run, I’ll correct the coordinates.”

“Confirmed.”

He barely heard the artillery strike. The M777 howitzer—nicknamed “The Three Axes” because the sevens painted on its side looked like axes—fired from far away, out of reach of the enemy artillery positions. His tablet offered a clear view of a shell taking out the armored carrier. An APC lit up and burned.

“The tank and the second APC are retreating! I’ve got the mobile coverage. Tracking.”

“I see them.”

“There’s only one road there, no turns. They’re retreating straight down it.”

“We’ll try to cover them. You guys wrap it up.”

“Confirmed.”

But they didn’t manage to wrap it up.

“Incoming!”

“Get down!”

The ground reared up and rushed forward. He felt the hit with his entire body, and then the darkness took him.

He’d gotten lucky, twice.

First, he lived through the attack. Second, he lost consciousness. Otherwise he’d have been screaming and suffering intolerable pain all the way to the hospital. There they’d pumped him full of painkillers. The pain was still there, but it was somewhere on the periphery, as though it weren’t his pain but someone else’s. He’d phased in and out of consciousness. He was diving, sinking ….

He finally resurfaced fully in a private room at a Hamburg clinic. Three surgeries. Rehab. What, an experimental model, you say? Not fully tested? Well, let me see. Wow, cool. My consent? Where do I sign? Yes, I’ve thought it through. Give me the papers.

Three months later:

“Mavic, is that you? Where did you come from?”

“Uncle Hans sends his regards.”

“I thought you were discharged?”

“What, and miss all the fun? No way! I procured a pair of new birdies, too.”

“Where from?”

“A flea market in Germany.”

“As you can see, the painting depicts the raising of the Banner of Victory on Malakhov Hill in Sevastopol. Of course, we dreamt of victory even in the early days of the war. But in this instance, the moment is depicted almost exactly the way it eventually happened in reality. The experts note the amazing coincidence …”

A coincidence?

Robbie, you knew, didn’t you? You knew, even then.

The group followed their guide into the next hall. Lesha leisurely approached and stood in his favorite spot, three steps away from the painting. He knew it down to the last blade of grass, the last crease in the camo pants of the master sergeant holding the yellow-and-blue flag in his hands.

The first—and last—creation by an AI who’d managed to peek into the future.

What was your starting point, Robbie? Back when you were a nameless neuronet? The drawings and photographs. They stayed with you, like childhood memories. Like a first love. Sorry, I seek out human analogies; they’re the only ones I’ve got. Perhaps the name I gave you played a part? Albert Robida was an artist and a writer first, and a futurist second. Creativity, art, intuition—those are methods of understanding, no worse than any others. A means to peek at tomorrow …

The source file of the painting in full resolution was still stored on Lesha’s computer. It had been his buddy, Lev, who’d stayed at Lesha’s apartment while he was in the army, who had kindly shared this file on the internet for the entire world to see.

He could enjoy the painting all he wanted without ever leaving home. Even so, he came to the museum once a week. The printout lured him in, though he couldn’t explain why.

Everything had happened as depicted. The Malakhov Hill in Crimea, spent cartridge cases strewn across trench parapets that were plowed by bullets. Bodies in the grass. A burned-down T-72 tank in the background. Rusted barbed wire. A master sergeant carrying a flag, amidst a group of exhausted warriors. Though in the end, it was Ilya Gluschenko and not the master sergeant who’d ultimately planted the flag at the top of the hill.

But everything else was accurate.

The prosthetic fingers gripped the flagpole. They were clearly visible, those bionic fingers.

The scarlet light of the security camera in the ceiling went out for a second. It lit up, flashed, shut down, and lit up again. Lesha was about to leave, but a small monitor installed next to the painting suddenly erased the artwork’s description and replaced it with a single line.

Lesha stepped closer.

Ten snowflakes. Three raindrops. And one mocking smiley emoji.

Having returned to the hall, the tour guide looked at the laughing man with disapproval. People shouldn’t laugh in museums: loudly, infectiously, childishly, disturbing fellow patrons. They shouldn’t shout, “Robbie! Robbie, you beautiful bastard!” while cackling.

The tour guide wanted to say something, but she held off. The man had a prosthetic hand. A lacquered-black, latest-generation bionic prosthesis with tactile feedback. He was probably a war veteran.

All the same, one should remain quiet in a museum.

Read the entire anthology here now in ebook or print formats:

https://amzn.to/3MEG0RK