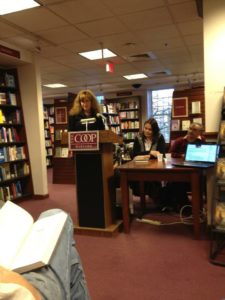

On the evening of April 19, 2012, Marina and Sergey Dyachenko walked into The Harvard Coop for a presentation of their novel, The Scar, that had been recently published by Tor. The audience was perhaps a tenth the size they had gathered back home—not entirely unexpected for a husband-and-wife writing team virtually unknown in the States—but, if anything, more enthusiastic. Marina and Sergey took it in stride; although their fame in Russia routinely brought hundreds of devoted readers to their readings, they were pleased to see even a dozen people greeting them at the iconic Cambridge bookstore. This type of response is very characteristic of the Dyachenkos. The authors of twenty-nine novels and countless novellas and short stories, prolific television and film writers, they seem to be utterly unaffected by stardom. They’re gentle people who spend most of their time in each other’s company and seem content with interacting with the world from the privacy of their writing space. They are active on social media and take time to read all and answer most of their fan mail. They’re particularly fond of any expressions of creativity sent their way, whether it is an illustration to one of their books, a song inspired by their characters, or an amateur translation of their work, which is exactly how I met them and how the story of the publication of Vita Nostra in English began.

I first came across their novel Vita Nostra ten years ago, attracted by its setting: a secluded school, an intellectual corral, where students grow and transform under the new realities they confront in their changing world. I love books about private schools or colleges—it’s such a rich setting explored by so many writers (Donna Tartt, and Joanne Harris come to mind, along with a newcomer M.L. Rio). Vita Nostra most closely resembles Lev Grossman’s The Magicians trilogy, with its technical, step-by-step approach to magic. I mentioned the book to Lev at his reading for The Magicians, he asked me to translate a few pages, and I ended up translating the entire novel mostly for his benefit; my non-Russian-speaking family members could now read it as well. Once the unsolicited manuscript was completed, I sent a courtesy copy to the Dyachenkos using the contact information listed on their website. Sergey responded with a lovely letter of thanks, and thus our friendship began. For a long while I could not quite believe that every few days a letter written by Sergey would appear in my email. It felt like a fragment of a new Dyachenko novel that only I was privy to, a gift from my favorite writers. I now had an opportunity to peek into their process and find out how they manage to create such nuanced, vibrant, flawed characters, a slice of reality in a fantasy setting. I also had the extraordinary opportunity to collaborate with Marina and Sergey: when, for legal reasons, we had to replace some of the literary quotes in the text, we worked together on choosing the appropriate passages from the Dyachenkos’ other novels, translated by me but yet unpublished. They allowed me to comb through their body of work and present what I thought was contextually fitting—a truly generous, unselfish gift a translator can only dream of. Vita Nostra‘s subsequent fate is a bit of a Cinderella story: the amateur translation went on sale as self-published book, gained devoted fans, and is now a Big 5 release (Harper Voyager, publication date November 13th, 2018).

Marina and Sergey write in the genre they call “M-realism:” magic realism may be implied, but Sergey wryly suggests that “M” stands for Marina. It is an unusual genre for the label-driven American publishing industry—while nearly all of their books can be classified as speculative fiction, the fantasy element is never the focal point of their work. The Dyachenkos’ favorite method is to introduce the fantastic early in the book and then make you forget all about it. In Armaged-Home the fantasy element is the apocalypse with its regularly scheduled occurrences. In Pandem it is the personified noosphere, ready and willing to lead the mankind to a higher level of cognitive awareness. The Scar is less of a magical adventure than an exploration of pathological fear and the consequences of human actions. Alyona and Aspirin (publication date 2020, Harper Voyager) is not about a girl from another world with a demonic teddy bear sidekick; it’s about the complications of loving another human being and about the challenges of mastering a musical instrument. Even the Dyachenkos’ children’s stories (which I am currently translating into English) offer complicated moral dilemmas layered upon sweet, simple plots: a river that longs to visit an art museum but doesn’t want to get the paintings wet (it ends up being wrapped in cellophane for one day), a tiny violin that never gets to perform in a real concert hall because, by the time her owners are skillful enough, they need a bigger violin (thankfully, a child prodigy comes along), a tractor whose caterpillars turn into butterflies and flutter away (the tractor wistfully wishes them the best).

Marina and Sergey love their characters and insist that some of them are autobiographical; and yet they show no remorse in doling out disasters and tragic circumstances. There is never any hint of Deus Ex Machina. The price is always unbearably high. Their protagonists may start off jaded and cynical (like Aspirin or Egert Solle) or innocent and naive (Sasha Samokhina or Pavla Nimrobetz), but they are invariably led on an odyssey to finding love. Crumpled pitilessly by the process, they reemerge stronger and infinitely more passionate. In one of their short stories, “Ace”, where the authors’ previous occupations shine through (Marina was an actress and Sergey, a psychiatrist), the protagonist—a young theater director—chooses to submit his work to a supernatural spirit of theater that can either sanctify his production or bury it. It is my favorite short story of theirs precisely because it is so dark and so despondent (and that speaks to my Russian soul), but Marina and Sergey insist that the protagonist’s suffering eventually leads to artistic freedom, and hence—a happy ending.

Marina and Sergey tell damn good stories—as speculative genre requires; it is their awareness of human character that ensures the crossover to literary fiction. Their books never push an agenda or a moralistic message at the reader. There is always a question, but never a definitive answer. If your fiance is abducted by a bitter vengeful spirit, would you fight for her and die in vain, or would you attempt to actually save her even if that means leaving her alone with the monster for what turns out to be decades (Screwt)? If you had the power to tie people to you and keep their devotion forever, would you use that on a woman whom you love and who loves you back, or would you step away to ensure that she always has a choice (The Valley of Conscience)? If you had been offered a perfectly comfortable existence as a second-rate citizen, would you choose to undergo a savage initiation process just to be considered a full member of a society that has no use for you either way (Migrant)?

Marina and Sergey favor open endings for the same reason. To this point, they once wrote two endings of the same story (“The Wing”), one hopeful but unrealistic, the other—melancholy but far more honest, and had the readers choose the one that suited them best. This was not a gimmick, or an attempt to create an interactive experience; Marina and Sergey simply could not agree on how the story should have ended. It doesn’t happen that often. Their creative process is a well-oiled machine: Sergey is in charge of dramaturgy, and Marina—of literary style. He offers a psychiatrist’s view of human behavior, and Marina provides her lyrical, poetic outlook. Sergey admits that, given the choice, he’d probably write about real people making realistic decisions under realistic circumstances. Gently yet steadily, Marina steers him toward alternate worlds where human aggression is channeled into a dream world, where jilted lovers twist themselves into a tangible essence of rage, and where inquisitors struggle with their love for unfettered witches. It is thanks to Sergey’s skills of writing solid plots that Marina’s beautiful aethereal worlds have such a strong structure, a foundation built on the characters’ flesh and bone, their blood and tears. Their ideal fantasy is a story of a real person in a chimerical world.

Sergey is the extrovert of the family, a vivacious and curious man who likes to heap praise on his friends, colleagues, and fans. He is an avid film enthusiast who somehow finds the time to watch and review just about every new film and television series released in both Russia and the United States. He is a world traveler and a hard-core gamer; his interest in the world is genuine and contagious. Marina, who looks like a softer, warmer version of Cersei Lannister, is quiet and introspective. While Sergey embraces you immediately, Marina’s trust must be earned. It is not a question of time or effort. Sometimes all it takes is a genuine human reaction. She once gave a hug to an acquaintance whom she met under difficult circumstances; “Your heart is beating like a little bird,” she whispered in their ear, recognizing the emotion and offering comfort.

When asked to describe their ideal reader, they pause and throw out a bunch of non-committal, seemingly irrelevant responses—an urbanite or a villager, not rich but well off, a dog lover who appreciates cats, with a degree in liberal arts but with a technical background, a lover of music, of literature, who favors sleeping in and likes rain. Then, in a sudden flash of insight: “It’s someone who likes to see a determined blade of grass grow through the asphalt,” they say.