He had a lot of work to do, a hell of a lot of work. Arthur barely managed to get the time off—in the end he simply backed his boss into a corner—either I get my twenty-four hours of leave or I submit my resignation—yeah, that’s right. And immediately switched tactics: come on, man, it’s my mom’s birthday, she is turning seventy, lives alone. Have a heart.

His boss didn’t have a heart but had plenty of brains. Get out of my sight, he said, before I change my mind. But I want you back here first thing Monday morning, bright eyed and bushy tailed at seven a.m.—no, six…! We’ve got a schedule to meet, a waiting line at the recording studio plus a new cameraman, and I need material ready for the evening show. Here, take these printouts, look at them on the way. Tweak the focal points, do your thing.

It was a nine-hour trip. It used to take four but now, after the Pact, there were not one but two borders to cross, plus the time difference.

The present was already in the back seat; Arthur stopped on the way to pick up a couple of baskets of fresh wild strawberries. Grandmas along this route knew the demand for these was high and did a brisk trade. But he had the money; his mother always enjoyed berries and they were good for her, besides.

He drove slowly but it was a bumpy ride nonetheless—the road was in bad shape, particularly once he passed the first border, which marked the beginning of the exclusion zone. Things were more-or-less bearable between Smushkovka and Suvoyi, but got downright rocky after that; it was out of one pothole and into the next all the way to Kopalni, and all you could do was just crawl along and enjoy the views of dried-out fields.

The locals usually took the round-about way through Kislyuhino and Turnovka: it took longer but kept you safer. Arthur never used the detour, preferring to go straight through Kopalni. To have a point of reference.

Once the Pact was signed, they kept talking about getting the road fixed up, but the talk wasn’t very convincing and Arthur had no doubt that nothing would change in the next couple of years, at least. Why would it?

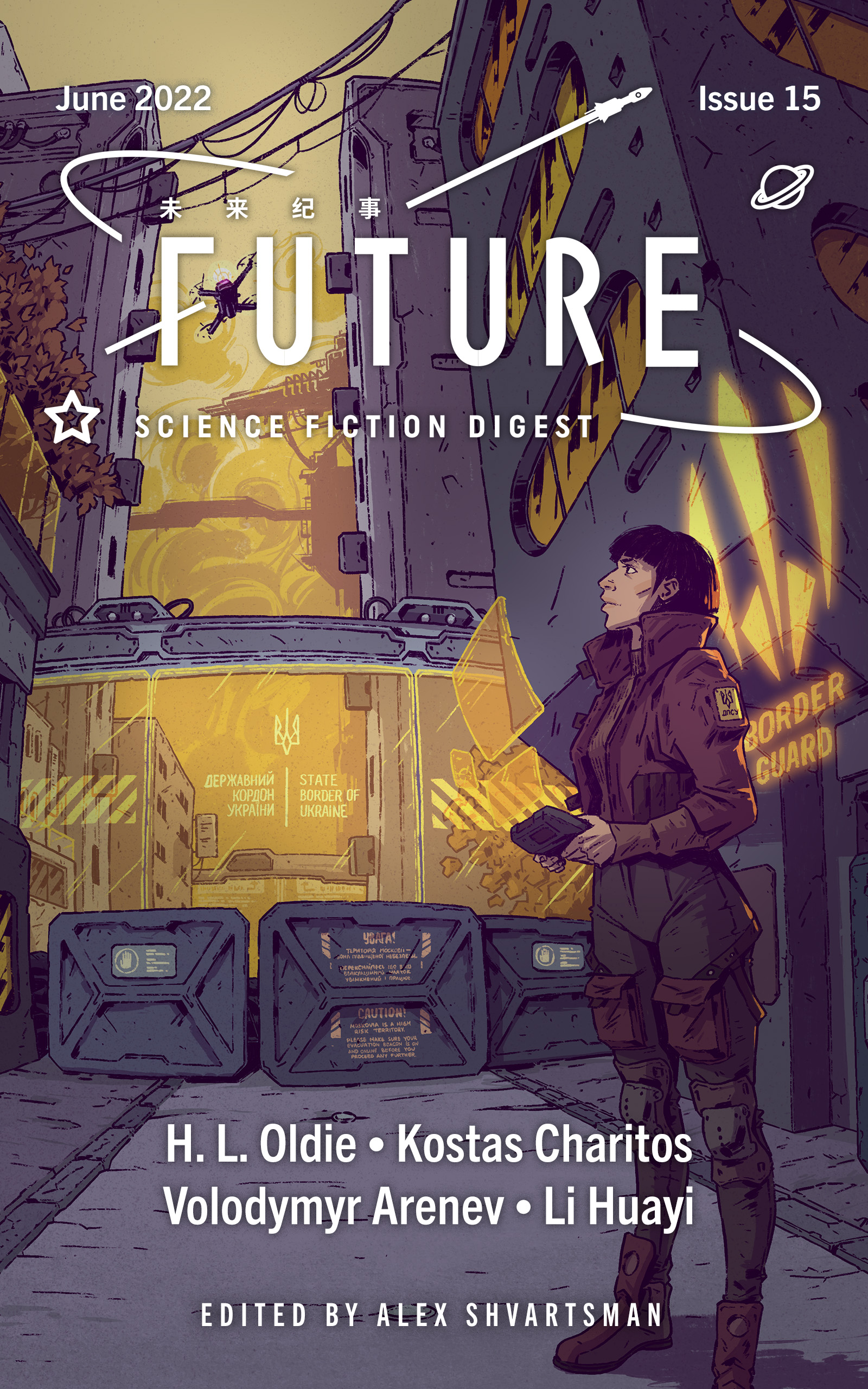

There was one positive in this: there was never a line at the customs checkpoint here. The checkpoint itself looked standard as could be: the road widened out to three lanes, the right lane was for continuing forward, the left for coming back and the middle one housed the control post itself. And there was also a small pocket over on the left side, this little fenced-in area. A “burp,” in local parlance.

Arthur was a familiar face here, but rules were rules—they had him step out, searched him, checked the car. Inquired politely whether he needed to use the restroom. He replied that first, he hadn’t eaten, and second, he had taken the pill.

Still, he pulled over to the right side after crossing, into an identical pocket, and spent five minutes with his sweating forehead pressed against the glass. Though, in retrospect, he probably should have lowered the window: it was fine now, and if the urge had gotten the better of him…

The border guards on this side watched him with a mixture of sympathy and surprise. They didn’t approach on their own and didn’t try to rush him either.

Arthur waited for the bout of nausea to pass, grabbed one of the baskets of wild strawberries and finally stepped out of the car. The smell on this side was that of a cesspit mixed with moist earth; fat, sluggish flies circled in the air.

They knew him on this side too—and he knew the rules of their game. He placed the small basket onto the wooden inspection table and handed his documents to the officer. While the sergeant studied his passport and visa, his older colleague quietly carried the berries off to the guardhouse.

“So,” Arthur said with a small cough, “how is the weather out here? I’ve heard it keeps pouring and pouring lately.”

The sergeant glowered at him and continued to thumb through the pages of the passport. He held the plastic card with the one-year visa pressed between his pinky and his ring finger, which for some reason gave Arthur a highly unpleasant feeling. The guy was green, with shaved temples and a tattoo on his left cheek. One of the “nutters,” as Mom referred to them.

“We’ve got dry heat on our side,” said Arthur. “Dry heat for two weeks straight now.”

“What are you bringing?” the sergeant nodded towards the car.

“Personal things.”

“Pop the trunk.”

There was nothing illegal in Arthur’s trunk. First aid kit, respirator, helmet, fire extinguisher, bulletproof vest. But the back seat had the box with Mom’s present in it and if this dolt decided to snoop around there and realized what was inside…

“Max, stop fooling around, let him through and come help me over here!” called the lieutenant. “This guy is falling apart.”

He was standing over by a car that had just arrived—a beat up “lug nut” with local plates. The driver had just opened the door and all but spilled out onto the pavement; the lieutenant grabbed him under the arms and was attempting to lift him up, but the guy was heavyset, and the lieutenant needed a hand.

The sergeant glowered at Arthur again. His cheek twitched and the praying mantis tattooed on it swung its blade-hands aggressively.

“Go on.”

He pushed Arthur’s papers into his hands and headed for the “lug nut.” “Ask him if he even took the pill.”

Arthur stepped to the side, pulled out and turned on his mobile, habitually swapped out the sim card. Then there was the sound of spinning blades and he watched as a big-bellied chopper with an official coat of arms on its side spilled out from exactly nowhere directly over the road. The helicopter hovered over the motorway, sending flags rippling and tops of trees swaying. Arthur snapped a couple of photos before the vehicle made a turn and took off back in the direction of Kopalni.

How do they even manage, he wondered, yet again. Regular people tend to spill their guts the moment they cross the dividing line, but they just shrug it off. Mishka Teptyukov used to laugh at that question. It’s very simple, he’d say: it’s all in your head. Those government types, they are all certified schizos: professional double thinkers, it’s in their blood, whether on this side or on the other. As if you don’t get it, Ozhigaev! You lot are essentially the same too, aren’t you? Well?

Arthur never argued with him. Mishka was a good drinking buddy, good for shooting the shit about chicks and all that. But arguing with him was pointless. Especially about this kind of stuff.

Besides, why bother? It changed nothing anyway.

Arthur exited the “burp”, made a U-turn and headed for Kopalni. The chopper stayed ahead of him for some time, then veered off in the direction of New Komarki. “Another self-important pawn with a working visit, par for the course these days. Making connections, restoring relations.” That’s what Teptyukov would have said.

Five minutes later Arthur pulled over, got the bulletproof vest out of the trunk, put it on, then stuck the helmet onto his head. This section was supposed to be safe, really, the last of the “ferrets” were holed up further out, in the local south-east. But occasionally they’d stumble into this territory too, mostly the ones that were sick and tired of everything. Ones that wanted to try and force their way across the border.

The road here was as bad as on the other side. Not identical, of course: the potholes were in different spots and there were more cracks. Although out here they had actually made a few attempts at patching them up, which he found slightly irritating.

The tanks were gone too—the rusty one by the entrance to Suvoyi and the other, burnt out one at the crossroads before Smushkovka. They had, of course, begun to clear out the road little by little after the Pact was signed, but the tanks had become a permanent part of the landscape, same as the tree stumps and the rocket craters that pockmarked the fields. But now they were gone.

The sides of the road were still completely deserted, though, even after he crossed the boundary of the local exclusion zone. There was some shaky fencing with warning signs everywhere, and insolent-looking rooks perched upon road signs followed his car with their eyes as he drove by.

He noticed people on a couple of the fields: they were spread out in a wide chain, each wearing some kind of odd spacesuit-looking thing. In front of them they held long poles with flat plates on the bottom. They stepped gingerly, lifting their legs high and taking long pauses, like herons wading, and swung their plates from side to side.

This was all a waste of time, of course. You had to have synchronicity for this kind of work, but with the time differences and without steady communications, how could you possibly attain it? Therefore, this could only be one of two things: a public spectacle or a novel manner of suicide.

He dropped by a supermarket in Proodki, then stopped for gas and to pick up a couple of local papers. The boy behind the counter attempted to hand him a pamphlet—a comic strip about ferret people, as it turned out. The artwork was atrocious, the writing—borderline illiterate; Arthur couldn’t understand half the phrases altogether. But he kept the pamphlet all the same, as an artifact.

Mom must have spotted him on approach because she was already standing next to the elevator: one hand on the railing, the other grasping the knob of a walking stick. She had aged so much in the last couple of weeks, he hadn’t expected that.

“Listen,” he told her. “Principles are great and everything, but health comes first. You need to see a specialist, get proper treatment, proper drugs, you know this, Ma, with your background. I can’t find anything for you on this side. All your people have left…” (or died, he thought to himself—mostly died, as a matter of fact). “Mishka did promise to get in touch with the right people, of course, but these are difficult times, and if they decide to take you to the capital, what then, how am I going to visit you there?... And we can’t delay much more, either, the de-synchronization keeps getting worse, the projections are shittier than ever.”

She didn’t want to listen, of course. Told him to shut up and get inside, that there were people waiting.

There were three of them: a pair of her old girlfriends from the third and fifth floors, and Grigor Moiseyevich from across the street. Arthur hadn’t realized there would be others. He kept forgetting about these girlfriends of hers, it was like a stubborn mental blind spot. But it was too late; he wasn’t going to take the box back to the car now. He left it in the foyer, took the bags of produce into the kitchen.

He listened and replied politely for the next hour and a half. No, everything is fine over on our side. The roads have been fully rebuilt. Everyone who wanted a new passport got one. No lines of any kind, you can make appointments over the internet. There is plenty of food. Berries? The berries are imported, but it’s cheaper that way. Please, please, have some!

A siren suddenly went off outside. He jerked and pushed over a bowl of sauce, which landed directly on his trousers even as he dropped to the floor. There shouldn’t be rockets, they’ve stopped bombing a long time ago, he thought, his face now pressed into the rug, eyes level with a pair of old feet in threadbare slippers. He couldn’t understand why the others were so calm about it. Have they really gotten used to this?

“Get up,” said Mom from somewhere up above. “You’ll get the rug dirty, what am I to do with it then?”

Right, of course. It wasn’t an air raid siren; it was just a car alarm. They had a new kind of alarm here—or rather just a different kind; it emitted a piercing, animalistic howl that sounded like some small and desperate beast trapped in a basement.

He went to the kitchen to try to clean off the sauce, realizing full well there would be a stain. He reached automatically for the radio, to turn it off—he couldn’t stand that endless, meaningless prattle—and suddenly froze.

The host was reading the news, something about the “Exclusion zone: a look from the future” convention, something about breakthrough research and unique projects. He was speaking surprisingly clearly and intelligibly, but Arthur caught himself thinking that he still couldn’t understand even half of what was being said. The words were familiar, but the meaning behind them was missing entirely.

This can happen sometimes, Tevtyukov used to tell him, you understand and don’t understand all at the same time. You can’t even clearly identify which words aren’t connecting. You just sit there like an idiot, trying to make out those shows of yours through all the interference of the Separation, and the language sure seems the same and yet—nothing. One of our foreign universities even coined a term for it, determined the basis, supposedly. De-synchronization doesn’t just impact a particular piece of the border, they say; Separation causes cognitive phenomena as well. Bottom line, no one really understands a damn thing, but they sure make it sound important. Again, it’s more of a localized problem, which occurs mostly in the immediate vicinity of the exclusion zone. And it rarely gets the locals: I suppose they have an immunity to it or some shit like that; but if you came to this same-said exclusion zone from a ways off, well then—giddy up. Now, who and for what reason is going to show up here from a ways off and still know the language well enough to understand—that’s a different question, isn’t it? Not why we split up in the first place, is it? I mean, sure, listen to your news for a bit and you start seeing red, but again, who here is going to bother listening to your news? Don’t even have to jam the transmission, Separation does the job just fine all by itself.

Right, thought Arthur presently, Separation… does the job… He shook his head, then, on an impulse, put his thumb against his ear and pressed a few times, hard.

Then he heard the door squeak behind him, he thought it might be Mom, but it was Grigor Moiseyevich. The old man was simply standing in the doorway, staring straight ahead, his funny, bushy eyebrows pressed close together.

“Listen,” said Arthur, “can you talk to her at least? This is just silly. And for what? It’s not like she was ever, I don’t know, some local patriot, some idealist, any of that stuff. The choice is obvious: I mean, sure, when they just launched the Separation everything was unclear and frightening and… The memories, they were too fresh. But it’s been half a year, everybody is happy, everyone got what they wanted, chose their own way forward. Sure, the region has problems, well, of course it does, after so many months of hammering… but they had told us straight away: the Separation won’t change the past, it will just offer everyone a choice. Two territories instead of one, nearly the same, but not quite, some things present here, others there, it’s got to do with the laws of nature, even when we try to break them we are really just tricking them a little, but you can’t seriously…”

He stopped short, realizing that the old man wasn’t listening to him, but simply studying him like one would study a chattering monkey at the zoo.

Arthur had zero memories of him, although obviously he came from somewhere, this Grigor Moiseyevich; Mom had always said that he’d lived here forever, in the building across the street… or on the next block…

“Fine,” said Arthur tiredly, “I get it: I am a stranger to you, a whippersnapper, what do I know? I fled to a comfortable spot in another country, a foreign country… But you love her, don’t you? Care about her? Then tell her to go, for her own sake, at least.”

The old man just stood there, watching, eyebrows raised.

Arthur realized it was all for naught, waved his hand in the air in frustration.

“Why do I even…”

And then the old man puckered his lips, shifted his chin and said:

“She will go.”

He added something else too, but Arthur was so taken aback by what he just heard that he didn’t make out the rest.

The TV was on in the living room now, some local channel, lots of interference. As a kid he used to blame it on their ancient Horizon set, but now Mom had a new plasma TV, he’d bought the latest model just a few years ago, right before the Separation. Tevtyukov had helped get it to her.

But Mom kept watching and those old women of hers kept watching too and they didn’t care about the interference one bit.

He sat down at the table, poured himself a shot, drank. He started thinking about where and how to get her set up, she couldn’t live with him, of course, he’d need to rent her a place—actually, at first, she could just stay at the clinic, she needed tests and procedures anyway, had to finally get her health in order, for Pete’s sake.

The relief from the thought that he wouldn’t have to make the trip out here ever again poured over him like a big, balmy wave. She might have bothered to let him know sooner, sent an SMS, he thought, with minor irritation—he wouldn’t have had to lug her present all this way.

But right now he couldn’t begrudge her the present; he dragged the box from the hall into the room and began to unpack it.

The old women stared at him in surprise, as if they couldn’t altogether understand where he’d come from. Arthur suspected that both had long lost their minds, or were well on the way, anyhow. He even felt for them a little. But there were lots of others like them in this region, which was no surprise—these people had gone through so much, lived under constant physiological and psychological pressure, under the threat of death, and it’s hardly any better now with all these “ferrets,” raids, sweeps…

He flinched, like from an electric shock, and scratched at his wrist.

“All right!” he said briskly. “Let’s get the reception going here, one moment.”

He turned on the antenna, clicked a few buttons on the remote. Located his channel; Chagovetz, his co-anchor, was right in the middle of that interview on the “mysterious pages of history” with that professor, the sweaty one, who swallowed his “r”’s. She had complained after that the man had kept trying to grab her hand.

“There,” said Arthur. “This is for you. An experimental model, the bleeding edge of technology. They gave it a dumb name, ‘Mother’s voice,’ but whatever. This thing lets you get our channels through the Separation. Remember, you complained that you can’t always hear me properly… well, here you go…”

His mother gave him a surprised look, as if she had no clue what he was talking about; she must have dozed off. A real paradox, if you think about it: you’d think the stuff they talk about on the news would give you insomnia for days on end—and yet, people seem to doze right off listening to it! Inexplicable!

“Ma,” he said, “can I have a minute, please?”

He walked back to the kitchen and momentarily stopped in his tracks: he figured Grigor Moiseyevich would still be there, listening to the radio or smoking by the window, but the kitchen was empty.

“So, you’ve finally agreed,” he said to her. “But why didn’t you say? I would have gotten the documents ready.”

She reached out suddenly and touched his forehead—just like when he was a child, whenever he had complained about a dry throat or sneezed.

“I don’t need documents,” she replied. “Everything is already taken care of. You won’t have to come here anymore—you won’t be able to, anyway.”

She mentioned a name then, which immediately slipped out of his mind, again because he was surprised, confused.

“…the capital. I didn’t want to, at first: your father is buried here… and you’ve been visiting, occasionally, at least… But he is right: it’s no use sacrificing your life for the dead. I… I had watched… I saw everything, I just didn’t want to believe it at first… and then I decided I had to, had to watch every show, because it was my fault, my fault for being a bad mother and I’d wanted… wanted…”

“Wait, wait! I can’t… I don’t… it must be that syndrome Mishka was talking about. Oh!” he exclaimed, “it’s Mishka, isn’t it, Mishka is coming to get you? Tendryakov? He’s got something for you in the capital? But why didn’t he… but, no, of course, he is always so busy: he is a big boss now, infopolitics, no laughing matter.”

He even felt a bit of relief—and then thought that everything seemed to be repeating and he himself was being repeated. Then he heard a voice from behind the wall, a very familiar voice, too familiar… He froze, then launched himself into the next room in one great leap, then froze again right at the threshold and the old women turned and looked at him, startled. And Grigor Moiseyevich—where had he come from?—got up and slowly moved his hand downward, downward.

“Put it down,” he said.

And then Arthur saw a big kitchen knife in his own hand, wet and slippery.

He turned, confused, saw his mother in the kitchen and let out a sigh of relief.

And then heard his own voice, again.

In the television. Right. Where else, he thought, where the hell else.

He went to the sink and washed the knife, in silence, he didn’t want to multiply the ghosts, because the other he, the television one, kept talking—talking about destroyed homes, mop-up operations, militants who seized people’s passports and locked them up in detainment centers—these hybrids of workhouses and temporary shelters for displaced persons—about atrocities ignored by the international community, hypocritical in its determination to whitewash and vindicate, about tears and pain and grief, from which some have been saved, at least, the ones that wanted saving.

He finished washing the knife and cut Mom’s birthday cake, but didn’t have any. He had no appetite and look at the time, besides… it was time to go.

He said goodbye, promised to call and to write—and extracted an identical promise in return. The capital wasn’t the end of the world, after all, if they could figure out how to transmit through the Separation then all the rest would turn out all right, too. And let’s not forget about Mishka Tverdyakov’s connections, besides.

Mishka could have warned me, the ass, he thought to himself. He had changed his clothes and was now trying to make his way out of the maze of inner courtyards. He got lost a couple of times: he hadn’t been here in a few months and look, they’ve dug everything up, started to lay new pipe, demolished the ruins of that old apartment block and began to construct something new in its place. I wonder, thought Arthur, how they’ve managed to extract the rocket shell from it; the thing is still there on our side, sticking out like a sore thumb. It was no use without synchronicity, our people had said: a public spectacle or a novel manner of suicide.

He drove around courtyards, hit dead ends, even ended up back at his mother’s building, except on the other side, saw glowing windows with shadows behind them and a man roughly his own age, or perhaps a little older, standing over by the building entrance. A familiar-looking figure, although he could not be certain—and he could not say what made him so frightened of this possibly familiar man, Mishka, it could have been Mishka, but no, not likely, Mishka did love Mom a lot, of course, like his own mother, basically, that was true enough, except he couldn’t have come here, couldn’t for a long time, and it was silly to go back and look. Besides, he’d finally found an underpass, a dark, black and narrow one; it felt like he was passing under a mountain instead of an old brick building—and on the other side was a familiar street, he knew the way from there and raced confidently ahead. He hit slow-moving traffic a couple of times and complete standstill once; he pulled out the folder with the script then and began flipping through it. It was kind of fun, actually, did the boss hire new mythmakers?—the story about militant gangs had a fresh ring to it, and yet felt passably authentic at the same time. He scribbled a few notes on the margins, added a couple of little touches—desks in classrooms, a streetlight at the intersection, a description of the militants. Neither the desks nor the streetlight matched current reality, but those watching the program will have remembered them—if they did at all—exactly like this.

Then he finally made it past city limits and gunned it for the border. It started to rain hard and he had to slow down. He stopped at a gas station just past Suvoyi, went to take a piss, and bought a couple of candy bars. He’d hardly eaten at his mother’s, had had no appetite, but hunger caught up with him now. He wolfed down one candy bar right at the counter, washing it down with a cup of local coffee—passably decent; and chewed on the other one while walking back to the car.

He had visitors waiting.

He even chuckled at first: they looked exactly like the characters he’d just outlined on the margins of his script not an hour ago. Three were basically still boys, the fourth—in his fifties, suntanned and sinewy, with a wolf’s stare.

“Your papers,” said the sinewy one. “Let’s see them, please.”

He flipped through them carelessly but took some time to study the card with the visa stamp. He passed it to one of the boys, nodded to Arthur:

“Your phone.”

“Zero nine seven…” began Arthur, but the sinewy one waved him off and clarified:

“Not the number—the device.”

The flop-eared kid with a buzz cut standing behind him adjusted the strap of his machine gun; the other one stepped sideways, positioning himself between Arthur and the gas station. Not that there was any hope of help from that direction: the attendant behind the counter was working very hard to appear engrossed in his smartphone.

They move around in groups of four or five, checking documents, recalled Arthur, looking for some small thing to pick on, then drive you onto mined farmland and order you to walk in the direction of the woods.

“Listen,” he began, handing over his phone, “I understand and fully share your… eh… concerns. It’s the border, these are troubled times, control is, of course, essential. But in my case, there is nothing to worry about, I assure you. I was visiting my mother. Today is her birthday, I can give you her number if you like and you can call and confirm.”

“When,” asked the sinewy one, not bothering to look up from the phone, “did you take the picture and for what reason?”

“What picture?”

“This one.” He spun the phone around and Arthur saw the smudged profile of the helicopter, tops of trees, flags. “Or was this a present for your mother? For her birthday?”

The youths grinned but uttered no sound. They were well-trained, self-assured. Cool as cucumbers.

“It’s just a picture,” said Arthur casually, “what’s it got to do with my mother? I saw the chopper exiting the Separation, wanted to catch the moment of transit. No one has been able to capture it, you know: no matter how many times they’ve tried they either get the moment before it appears or the moment after. There is a substantial prize for anyone able to catch the stage in-between.”

“A prize,” nodded the sinewy one. He flipped through a couple of more shots with his finger, then dropped the phone along with the passport into his front breast pocket and said softly:

“Come with us, please, we need to confirm a few details.”

And then added, suddenly:

“You did get to say happy birthday to your mom, didn’t you?”

Ok, just don’t panic, said Arthur to himself. These types, they can smell fear. Act confident, not arrogant, but not sycophantic either. You are a leading journalist on a national television network, a public figure, if anything happens they are going to come looking for you. And they will get you out, Mishka will stand the whole country on its head, he’ll rip out their guts and hang them over their fucking ears but get you out he will. Good God, where the hell did they come from, anyway?! It’s been peace here for over a year, all the “weasels,” “cranes,” and “salamanders” have been basically cleared out and the rest have been absorbed into the armed forces, legalized, placed under control; whatever stories the mythmakers may weave to order, you know the reality perfectly well. So who are they then? Some stray remnants? Or something new we haven’t gotten wind of yet?

“I did,” said Arthur. “I did talk to my mom, but I’d also meant to phone an old friend, but didn’t get to it, forgot. Mikhail Tendryakov, have you heard of him?”

They exchanged looks and Arthur realized immediately that he’d made a mistake.

“Teptyukov?” confirmed the sinewy one. “Mikhail Gennadiyevich Teptyukov, from the Ministry of Infopolitics?”

He kept mutilating Mishka’s last name for some odd reason and his speech suddenly became slurred, mangled, he began to swallow words and even occasional phrases.

“…the one that was part of the delegation when the Pact was signed?... six months later, in the spring… negotiated for those schoolchildren… made a deal with the “bustards”… a scar right here?...”

“Yes, yes, that’s him,” nodded Arthur, almost irritably. He couldn’t understand what the sinewy one was trying to insinuate.

“A friend, is he?”

“Yes, a childhood friend. Even though we live on different sides, we stay in touch. Some things are more important than the Separation.”

“Get in.” The sinewy one indicated the car with his chin. “We’ll show the way.”

And then he knew that this was it. Mishka would indeed look for him, perhaps even find him. Somewhere in the woods along the border. He would identify him by the scar beneath his shoulder blade and ensure he received a proper funeral.

He suddenly visualized Mishka’s sarcastic face, his crooked grin: how about it, brother, how did that body armor work out for you? And the helmet?

Arthur thought of the fire extinguisher: maybe he could make up an excuse to get it from the trunk, spray one of them in the face, throw it at another, but what about the rest of them? Was he hoping that they don’t know how to use those guns? That they’ll miss? That he might just be able to jump behind the wheel and drive away, even wounded?

He opened the door and climbed inside, one of the youths was already getting comfortable in the passenger seat, knees splayed out wide.

Now, said Arthur to himself, it’s happening right now.

He turned the key in the ignition, looked behind him, wondering what was keeping the others.

The sinewy one was talking on the walkie-talkie, frowning, facing out towards the road. There, at the entrance to the station stood their car—a beat-up military jeep, with flags and a teddy bear on the roof. The teddy was extremely dirty, you could find better at a garbage dump.

“Right,” spoke the sinewy one into the walkie-talkie. “Needled, all four of them? In which one? Ok, question the neighbors, we’ll be there in seven to ten, yeah.”

He motioned with his shoulder, continuing to ask more questions; his boys turned and ran for the Jeep. The one sitting next to Arthur turned, inhaled, and threw open the door.

The sinewy one stepped to the car, shifted the machine gun so that it pointed directly at Arthur’s face.

“Never,” he said, “use his name for protection.”

He slapped the roof, turned, and jumped into the passing Jeep.

It suddenly started to rain again—a cold and ferocious rain, Arthur reached to close the passenger door, then realized that he’d been left without his passport and his phone and cursed loudly, wholeheartedly.

He reversed and only then noticed a pair of rectangles drop down from the roof onto the wet asphalt. Passport and visa. He hopped out, picked them up, and hoping against hope checked the roof, but there was nothing else there, of course.

When he approached the border, the road ahead was barely visible. The rain pummeled the hood, the windshield, and the wipers could not keep up so he finally turned them off and just drove.

He forgot to take the pill, so he spent a long time in the pocket past the Separation. He finally got back into the car, rinsed out his mouth with water from a water bottle, trying to wash away the taste of coffee and candy bars.

“It’s always the same with you guys,” said the officer on duty. She was standing there, smoking, looking past Arthur toward the border. “We’ve got all these signs, reminders, but every other Joe thinks he’ll just make it through on dumb luck, somehow.”

Oh, I made it through on dumb luck, all right, thought Arthur to himself. You’ve got no idea how lucky I am.

“How is it there?” she asked. “Raining, I bet?”

Arthur ran a hand over his wet hair and nodded. Shook loose a cigarette from the pack, clicked the lighter. Had an immediate coughing fit, spit out the cigarette and crushed it under his heel. At least he had the presence of mind not to toss it into the grass, it was still match dry here, one spark and it would all go up in flames.

“Where is the logic, I ask you?” The officer clearly had the time and the inspiration for a little tongue-wagging. “People get through, no problem. Helicopters, cars, carts. Hedgehogs run back and forth every single night, we’ve literally started recognizing their faces now. And our cat?—they feed her on their side, and we feed her on ours, she is eating for two. But clouds?—no can do. What do your scientist types say about it?”

She’s recognized me, then, he thought. Well, sure enough, everyone watches TV.

“Scientists say the Separation will continue.”

“That much I know myself,” she waved him off. “The zone keeps growing wider; they’ve moved us three times just in the last six months. I’ve heard they are working on movable buildings: gatehouses, scanners, latrines, all that stuff. But it’s going to stop growing sooner or later, isn’t it?”

“Definitely.”

She chuckled.

“You all say that. ‘Definitely,’ ‘it’s under control,’ oh, and ‘it’s for the better.’ Like, the other side is such shit that the farther off we are, the safer we’ll be. But none of you really know anything, not any of you.”

“And you would prefer… the other way? Their way?” He was really interested now.

The officer turned to him. The skin of her left cheek was brown, uneven. And she had a black patch over one eye, total pirate style.

“Yeah, right! ‘Their way.’ When you people… I mean, our people showed up, I told my husband straight away: let’s pack our shit and go. You can’t go against the natural order of things, it’s like an avalanche or a flood. No one argues against a flood, and an empire is no different, is it? But when they launched the Separation…” She shrugged with one shoulder. “I have a sister there, my big sister,” she admitted suddenly. “And two of my nephews, six and eleven… well, back then they were. They’d lived right where the boundary came to be, didn’t want to leave until the very last: ‘it’s our land’ and all that. They come at night sometimes, when there isn’t anyone around.”

“Who does, your nephews?” he asked, confused.

“No, the others. The others who got caught in the Separation. They stand right there and watch. They just fucking stand there and watch and nothing else, ever. That’s why I always try to get the night shift. But I’ve never seen my own. You haven’t seen them, have you? When you passed through?”

She pulled a folded, laminated photo from her breast pocket. Arthur looked at it: a couple of very ordinary children and a very ordinary woman; even if he had seen her, he wouldn’t have remembered.

He shook his head, apologized, and got back behind the wheel. He had to be at the studio at six a.m., he wasn’t going to get enough sleep, he’d have to run on coffee, and he’d promised Chagovetz dinner in the evening, had been promising it for over a week.

“Or maybe,” said the officer, leaning over the car, “maybe he was right, that Teptyukov guy? We let others sort things out for us, accepted foreign technology, but even the Chinese themselves have no idea how this damn thing works. They just used you and us as lab rats, took our territories and voila. Maybe if that fanatic hadn’t killed him, Teptyukov would have found a way? To freeze the Separation, for starters, and then to shrink it away altogether? There has to be a way, don’t you think?”

Sure, he thought, as he drove out onto the road, and also a way to return the dead to the living, all these nieces and nephews, brothers, sisters, best friends. What does she know, this oaf? Teptyukov stuck his nose where he shouldn’t have and paid for it. “Fanatic!” At least they believe that—though why wouldn’t they, they watch TV, don’t they?

The hell with him, with Teptyakov, he thought with irritation. An old friend who played other people’s games. A traitor. Mom’s favorite.

Arthur found a pack of cigarettes in the glove compartment and finally lit up. He thought of Mom as he drove: it was good that she had stopped suffering at least, she couldn’t have held on for much longer, sixty-eight was a decent, respectable age. We all talk of living to a hundred and two, dream of hanging on as long as possible, but to be perfectly truthful, when you are suffering morning till night, day after day, isn’t it simpler… like this? Simpler and more honest, and easier for everyone involved.

Sure, he felt a sense of relief, but he had nothing to blame himself for, really. He’d kept on with the visits to the very last, brought presents, helped with money. Kept trying to convince her to move, even though he knew it would mean a myriad complications for him. And he had to keep listening to her go on about precious Mishka, her perfect son, even later, after the funeral, she kept repeating those stories over and over again, drove him absolutely nuts.

He’ll have to take care of the grave next time, he noted to himself. Procure a decent but modest tombstone, find a respectable photograph to engrave, arrange for a nice epitaph in cursive. From your loving sons.

Make sure you don’t forget, he told himself, even though he knew he wouldn’t be coming back there for a while.

There was a lot of work ahead—so much very important work, which no one but him could even finish, really.