In the center of the zero-gravity lab, in which I was alone, a wind with the salty smell of the air eighty meters above the East China Sea was blowing at 50 kph.

Floating with my body parallel to the floor while I was controlling the wind, I placed a hand on the titanium cage surrounding the round, two-meter observation stage in the middle of the room, and pulled myself toward the blue glow inside. It was interesting how my fingers on the inside of the cage felt a slight gravitational pull.

On the stage where the 50 kph wind was blowing, the gravity was also matched to the 0.973 m/s2 of the sky above that specific region of the ocean.

In the center, a swallow I’d named Akane was flapping his wings.

I’d messed up when it came to the gender. It was after I gave him the Japanese female name Akane that I realized the swallow that had been sent from the Philippines was male.

Behind Akane was a breathtakingly sparkling blue sky, and the deeper blue of the sea—projections. I knew the same sky and sea were being projected on my fingers and face.

As I watched Akane beating his wings with all his might, the wind suddenly whipped at my face as it changed direction.

Turbulence.

Akane was blown toward my side of the stage.

When I murmured, “Begin log,” the brain activity captured by the fMRI sensor fixed to the cage was overlayed on top of Akane. Of course, the video was an augmented reality only I could see.

I climbed up onto the stage, and, resisting gravity for the first time in a while, peered into Akane’s face. With the East China Sea projection-mapped on my own face, he couldn’t see me.

I saw a yellow spark shoot in C12, the region that governs a swallow’s migration.

Neurons firing.

The yellow spark born in the C12 region traveled as a signal to the bases of the wings and tail.

A twitch of his flight feathers shifted Akane’s posture, and he headed back toward the center of the stage. Watched from the ground, the action appears smooth, but if you observe the nerve movements from this close, you can tell they’re a set of digital motions.

With the signal of just a few hundred synapses firing, Akane can set his course and fly. The event is practically a reflex, bearing little resemblance to thought as we humans think of it.

Why do animals migrate?

After extinct Japanese eels were hatched in an ocean trench off the Philippines, they swam for Japan’s rivers, and wildebeests endure hunger and thirst to traverse half their great continent. Sea turtles return to the beach of their birth after two or three years of ocean living.

Of course, we know the reasons they do it. They travel for food, or a breeding ground, or in response to seasonal climate changes.

But—just as I thought that, there was a movement on the horizon line crossing my face.

Pulling away to look at the screen, I saw a stratovolcano with a beautiful base showing up small. This was the Fuji of Satsuma, Kaimondake, which towers at the tip of the Kagoshima Peninsula.

Little on the horizon, Kaimondake was a hazy purple through the steam rising from the Japanese Current; I gasped at the sense that I was really there.

I was sure that if it felt this real, even Akane would be tricked.

I slipped out of the gravity-equipped stage, and pushed off the cage with my feet to fly through the lab’s zero-G space over to the apparatuses fixed to the wall.

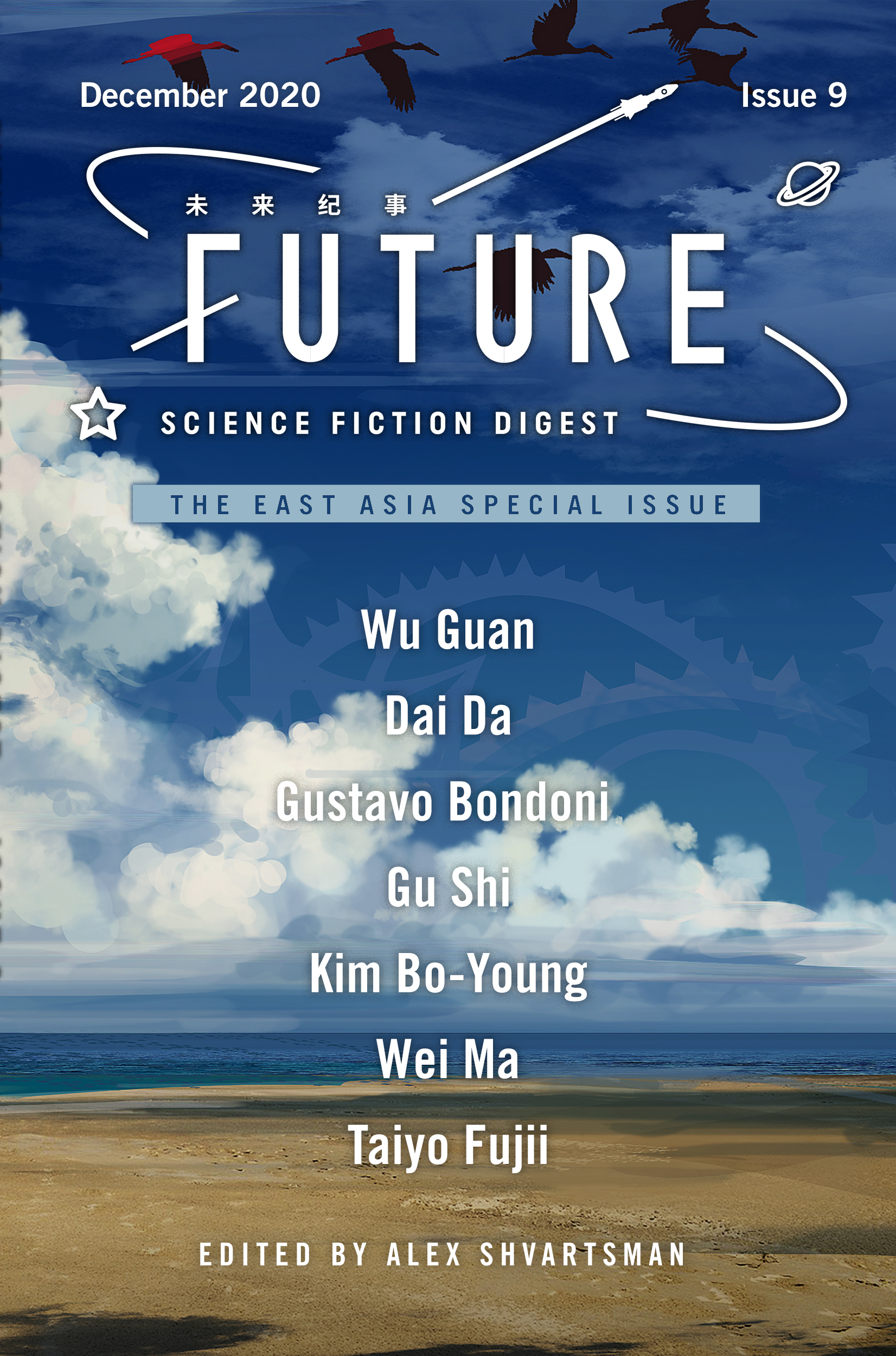

Trapping a migratory bird in virtual reality and observing its trip was my research. I’m second-level professor of Zhejiang University’s Institute of Natural Engineering, Tsukasa Hibino.

By placing a stage with gravity controls capable of reproducing slight geoidal variances at the center of an omnidirectional projection-mapping screen and blowing a wind comprised of minute, custom-printed atmospheric particles, I was reproducing the swallow’s migration from the Philippines back to Kyoto in its entirety.

Gazing between my floating feet, at the stage filled with the shining ocean, I refocused on the life-sized augmented-reality video of Earth, a meter in diameter, floating beyond it.

I was on a space island.

Once called space “colonies” or “stations,” an island is a human facility for living in orbit. If not for the zero gravity, it would be impossible to reproduce a specific geoid. In labs on Earth’s surface, you can’t fabricate gravity lower than your location, but here on Taiji Tianlou, with its graviton spiral accelerator (GSA) emitting two trillion gravitons per second, it’s possible to create as much gravitational interference as you like, anywhere on the eighty-five-kilometer facility.

I made use of that to reproduce a perfect East China Sea inside the lab.

The experiment was proceeding favorably.

If the setup worked this well, maybe next I could do a huge aquarium to investigate tuna or krill migrations. If I continued expanding the area of my research, maybe I’d be able to study the near-life phenomena we were finding on planets outside our system.

Then we’d get a better understanding of what they are.

I noticed a few streaks of light fly away from the Earth on the wall.

The thirty million Chinese people who had returned to Earth would be arriving home to Taiji Tianlou the next day.

And then the Earth would recede.

Its plane of revolution and Taiji Tianlou’s orbit around the sun at a tilt of thirty degrees mean we only approach the planet once a year. The date we come nearest is controlled by the huge number of gravitons being emitted by the heart of Taiji Tianlou, the GSA. This year, 2120, it was January 30.

Looking at the label on the streaks of light headed this way, I laughed in spite of myself.

“Chunyun Special.”

Even in the 22nd century, the Chinese living on space islands make the annual journey home for Lunar New Year. It goes without saying that those living in stationary orbit, such as on space elevator stations, go home, but those on Mars do, too. Supposedly there are something like seven hundred million or a billion of them, and, thanks to the space travel infrastructure improved to service their annual travels, it has gotten much easier to travel to and from Mars.

Though I belong to Zhejiang University, the reason someone like me, from the minor nation of Japan, can live on Taiji Tianlou, to simplify it quite a bit, is the rocket network built for the Lunar New Year trips.

“A million thanks to the kakyō,” I found myself murmuring.

The Chinese living in space have been called kakyō since the middle of the previous century. The second kanji in the compound is from an archaic version of the word that meant “Chinese merchants abroad”—the previous character had come back into style since the crowning radical is the same as the one in both characters that make up the word for “space.”

I searched for the Chunyun Special Flight that had departed from Fujian Spaceport and dropped a pin.

My friend from college, now living with me on the island, lab engineer Hefei Ye, was on that rocket.

As I touched the augmented reality with a finger, the “He’ll never agree...” slipped out.

I hadn’t even asked the question, but I knew he wouldn’t react well. I reread the message I had received the previous day.

“Hey, Hefei Ye. I think of Taiji Tianlou as my second home. If I were to return somewhere, this place would be fine. And when I move to the next place, that’ll be my home.”

Imagining Hefei Ye sitting in the cramped rocket seat, and his face, I voiced the question I wasn’t sure if I could ask:

“Why does it have to be Fujian for you?”

“I’m back.”

With a whoosh of compressed air as the plug door opened, a familiar voice echoed in the room.

“Good to see—whoa!”

When I turned around, my field of vision filled with him as he leapt from the door. He wasn’t used to the gravity, which was set to only half of Earth’s.

“Sorry!” Hefei Ye shouted as he tackled me.

I took his fingers from my shoulder and gently bent them backward.

When his arm extended reflexively, his back, rounded from his two weeks at home, naturally straightened as well. That stabilized his posture after he had lost his balance.

“Sorry, I’m not acclimated.” He scratched his head sheepishly.

“That can’t be helped. You were on Earth for two weeks. Welcome back.”

“Thanks.”

We hugged now that he was standing up straight. Whenever he was freshly back from Earth, his hugs were always a little forceful. Feeling my breathing get constricted, I yelped in spite of myself.

“Sorry, did I hurt you?”

“Not as bad as all that, but you could watch your strength.”

“Right.”

Releasing his arms, he was about to turn toward the container he’d left near the door, but I sandwiched his cheeks in my palms to stop him.

“You can unpack later. I’m going to make tea—which do you want?”

“I’ve had too much Wuyi and Maofeng, so I’ll have Japanese tea.”

I told him okay and readied tea cups and a small pot while trying to think of the best way to broach my topic.

After three minutes, the room was filled with the aroma of green tea. Hefei Ye and I sat across from each other at the dining table and chatted about what had happened over the past two weeks.

Once I had made our third cup (I can never get Chinese people to understand, but when making Japanese tea you need new leaves each time you add hot water), I was finally able to bring up what I needed to talk to him about.

“Do you remember Uluru?”

“It’s a settled planet in Cetus, right? Or was it Ophiuchus?” He sounded nervous as he asked.

I nodded and pretended not to notice. “Yeah. The fourth planet in the Tau Ceti system, Uluru.” I pronounced the name, which was neither English nor Chinese, respectfully, with the correct intonation. Uluru is named after a place sacred to a group of Aboriginal Australians.

The Australian planet development company, based in the New Sydney district of the space island La Grange 2, chose five thousand Aboriginal Australians to be the first immigrants and later the administrators.

I don’t know why they specifically chose people with aboriginal roots as immigrants. Maybe the president of the development company, with roots in Victorian England, felt guilty for the massacre his ancestors committed against the indigenous peoples, or maybe it had something to do with the anti–orbit globalism movement troubling space islands here and there. But since the company that sent the ship off went bankrupt, there is no longer any way to investigate its management decisions.

The ship departed twenty-seven years ago, when it was still the 21st century.

Regardless of the how or why, the Aboriginal Australian immigrants headed for the fourth planet of the Tau Ceti system, 11.9 light years away, using a graviton disruption lens to navigate a black hole fall. Having achieved ninety-nine percent of the speed of light in three years, the immigration ship reached its destination fifteen years after departing. Time moved more slowly on the ship itself, traveling at near-light speed, so only seven years passed inside.

Taking the same three-year period as they had accelerating, they decelerated to Tau system orbital speed and put the ship in stationary orbit as set out in the Exoplanet Development Agency’s terraforming procedures.

Looking down on the fourth planet with their naked eyes for the first time, the immigrants were captivated by the earth, orangey with a thin layer of mercury sulfide and sparkling through the primarily methane atmosphere. I heard the color and the giant landmass, visible even from orbit, reminded them of the huge sacred stone Westerners had once called Ayer’s Rock.

Along with notice of their arrival, the immigrants reported to the Earthsphere that the new land, which had hitherto only been known as “the fourth planet” would be called Uluru, and that their capital, of the moment, at least, would be named after another sacred place, Kata Tjuta.

This had happened twenty years ago.

The news that took eleven years and eleven months to cross space and reach Earth had arrived two weeks previously.

I had stopped Hefei Ye as he was packing for his Chunyun Special Flight and told him about the new planet humanity had reached.

He said that even in his home town, the kakyō who had returned from orbit had gathered and discussed it excitedly.

How would resources be brought into orbit from Uluru, which had four times the mass of Earth? How many space elevators could be built? Was terraforming possible? And if so, how would the earth, coated in orange mercury sulfide, and the primarily methane atmosphere be replaced? And would it be possible to shorten the fifteen-year voyage from Earth? That the conversations didn’t stop at the fantasizing of technical experts is the formidable thing about the kakyō.

During the two-week Chunyun period, the number of planet development corporations registered in China topped five thousand. When Hefei Ye VR’d me from home, he had winced as he said, “Ninety percent of them will dissolve, though,” and then told me he had even joined two ventures related to space flight systems as technical officer.

The two of us laughed at how quick to heat up and just as quick to cool down these off-planet Chinese entrepreneurs are, but then again, if five hundred companies remain, all I can say is that I’d expect nothing less from kakyō.

The space island where we live is supported by kakyō technology. The recycling plant that closes our resource cycles, the gravitational field navigation that makes it easy to change the orbit of our eighty-five-kilometer space island, the graviton disruption lenses with plasma trapped inside that make tiny nuclear fusion reactors possible—all invented by kakyō. They’ve filled the area this side of Mars’s orbit with space islands.

It’s even said that the lingua franca in the field of technologies related to living in space is Chinese.

But the further you get from Mars, the less you feel the kakyō presence.

Japanese space immigrants—nikyō—are working hard in that treasury of resources, the asteroid belt; the ones pumping up the Helium 3 that fuels nuclear reactors from Jupiter and Saturn are American energy conglomerates, and the same Arabic corporations that had dealt in oil in the Middle East.

The ones who sought a way out of the solar system were the European Union, the island nations of the South Pacific, and the Australian company that bet its fate on developing Uluru.

Kakyō have the largest share of the market for fusion reactors, GSAs, the most comfortable residential plants, and so on, but you rarely see any of them in person outside the orbit of Mars.

The reason—those of us living in the space age laugh as we explain—is that they won’t go anywhere they can’t get back from for Lunar New Year.

Of course, that’s a joke, but as Hefei Ye enjoyed his first Japanese tea in a while, I couldn’t manage to bring up the important thing I had to discuss with him. That said, there was no way he would overlook my hesitation.

He set his tea cup on the table and looked at me. “So, what about Uluru?”

The tea in his cup seemed to sway endlessly due to the gravity of only .6 of a G.

When I didn’t say anything, he smiled and offered a topic. “Now that you mention it, the second report from Kata Tjuta hasn’t arrived yet, huh? The gravity wave transmissions with the Tau system can send a megabyte per second, was it? They haven’t finished downloading the initial survey results yet, or something?”

You’re so nice.

I had looked it up a thousand times, but still couldn’t say it smoothly, yet here was Hefei Ye with the name of Uluru’s capital and the transmission speed off the top of his head. He must have looked it up just now in order to stay on the topic of Uluru. He must have noticed I was lost for words.

At any rate, I replied. “Yeah, seems like they haven’t managed to download it all yet.”

Hefei Ye seemed relieved and continued down that line of discussion. “We knew from the advance survey that there was no civilization using gravity, electromagnetic, or space-time waves, right? Any remains?”

“Apparently they found some structures larger than a meter as deep as 20 meters underground.”

“Any trees or anything? The drone photography showed something that looked like cedars, remember?”

“Those ended up being mercury sulfide crystals. Hexagonal pyramid-shaped fractal structures. Did you see the enlarged photo?”

“Would be neat if they could be sold as Uluru Crystals or something. So there was nothing organic?”

“Not more than what’s created in lightning strikes. We know there are bubbles of fat floating in the inland waters, but no self-replicators, like RNA, have been found. There are different colors around high-energy craters.”

“So the stage where something might become life, then. Have the seas been surveyed yet? There’s an ocean of water, right?”

“Yeah...they’re doing a survey of the ocean.”

Perhaps noticing the awkward pause in my reply, Hefei Ye leaned back in his chair. “They found life or something like it? Is it still confidential?”

After nodding, I swiftly shook my head. “Sorry, it’s not actually classified. I think the release will be out this week.”

“Is there life?”

This time I nodded slowly. “It’s not confirmed yet, but they say they observed something moving against the sea current from Kata Tjuta.”

“From Kata Tjuta...you mean from stationary orbit? Something big enough to be seen from 40,000 km above was moving down there?”

“Yeah. The movement would be comparable to krill on Earth, mass-wise.”

“Tsukasa, I thought you worked on swallows; do you do marine animals, too?”

“My specialty is animal migration. Uluru’s axis wobble is fast, so in a revolution—a year—there are three or four summers. Apparently that matter migrates between the north pole and the equator between summer and winter.”

“Just like migratory birds?”

“Yeah. Which is why the government of Uluru reached out... Will you come with?”

He dropped his gaze to the floor.

I knew he wasn’t hanging his head because he couldn’t answer. Hefei Ye wasn’t that much of a wimp. He looked toward the floor to look through it—to confirm the location of home, which was ten seconds away by lightspeed.

From Earth’s orbit, it took eleven years and eleven months to get to Uluru.

At the fastest speed in the universe—light speed—by electromagnetic waves, or even gravity waves, the fourth planet in the Tau Ceti system, Uluru, was eleven years and eleven months away. If you took one twin from a pair of entangled particles and put it there, the states of both particles would be determined simultaneously, but no information would be transmitted.

Raising his head, Hefei Ye tightened the corners of his mouth and asked, “Did they decide how settlers would be adapted to the environment?”

I brought the message to settlers up on my workspace and read off the gene therapy they would receive upon arrival to Uluru. “Resistance to harsh environmental exposure is required. VEMG.”

“Vacuum, electricity, magneticity, and gravity? The first immigrants to an exoplanet will live on a station, so I guess that makes sense. Even in the Earthsphere, lots of the builders get those. What else?”

“ATP chain reactions will be altered for methane respiration.”

“You have to?”

“While they’re doing remote surveys from Kata Tjuta, it’s not required, but once they switch to surface surveys, it’ll be necessary.”

“Wow,” he murmured, his breathing slightly erratic.

The gene therapy would replace all the mitochondria in my body to switch my carbon dioxide metabolism to a methane-based system. If you want to breathe in Uluru’s atmosphere without a pressure suit, it has to be done.

The cost would be covered by the autonomous government of Uluru, of course. It put pressure on their budget, but it was more realistic than terraforming the whole planet. More importantly, the massacre of all indigenous life would be unforgivable. But switching your metabolism at the genetic level causes another problem.

Stabilizing his breathing, Hefei Ye looked me in the eye. “So you’re quitting being human, Tsukasa?”

I couldn’t say anything.

You change species.

Of course, it’s not as if Uluru would be the first example of this.

As of the year 2119, on the fifteen exoplanets humans have settled so far, we’ve witnessed the birth of humans who breathe fluorine, humans who use ammonia instead of water and tolerate extremely low temperatures, humans who have traded carbon for silicon to support electric metabolisms, and more. The methane respiration therapy I would undergo was already in use on two planets in the Teegarden starzone of Aries. There were already 100,000 of those people, and two generations; their subspecies had been named Homo sapiens methanum spiritus.

They’re incapable of having children with the current humans, Homo sapiens sapiens.

“Wait, I haven’t decided for sure that I’ll do it.”

“But you will, won’t you? You’ll be studying life forms. Everyone else’ll be breathing methane and you’re gonna lug an oxygen tank? You’d need an oxygen chamber to sleep in, too.”

I couldn’t argue. Though I’d been invited, I was only a single researcher. Surely at some point I would have to stand on Uluru’s surface and breathe methane.

I made up my mind and said, “I guess—” but Hefei Ye spoke first.

“Why do you have to go as far as gene editing?”

“Because there’s no coming back,” I retorted.

Hefei Ye looked puzzled. “What?”

“Because once you go, there’s no coming back.”

I’d been thinking about this ever since I heard from the Uluru government, so the words came out smoothly.

“Trips to new exoplanets are one-way only. Uluru just got a station put in orbit twelve years ago, and it’ll be another fifteen before they have space elevators to pull resources into orbit. They can’t be bothered about building ships to get back to Earth. Even if they start, it won’t be for another half century or so.”

“If you could

come back, you’d stay human, you mean?”

“Yeah, if I thought I could come back to the Earthsphere...” I tried imagining

it. If people who went to an exoplanet could return to live in the Earthsphere,

if I could come back to live in this room on Taiji Tianlou again... “I’d

probably lug the tank. I’d put a pressurized base on the surface.”

I looked at Hefei Ye. Now it was his turn to fall silent. He didn’t have any other words to persuade me.

“Let’s go.”

“Mmm...” he trailed off.

“Let’s go. I want to go together. If I can live with you, then I can stay on Kata Tjuta forever.”

Hefei Ye didn’t answer.

Five years later, on the day of my departure, Hefei Ye was not beside me.

I boarded the second immigrant ship, dubbed the Birrarung Marr, alone and headed for Uluru along with five thousand others.

The voyage aimed to be “as diverse as possible,” so it included five hundred kakyō who had given up their customary Lunar New Year trips.

We were traveling for six years, so I fell in love during the flight. By the time we reached Uluru, I had just ended the relationship with my second partner.

The first was an agricultural engineer from Germany. We dated for quite a while and had fun, but around the middle of the trip, he got busy, and our relationship cooled off and faded away. The second was a kakyō by the name of Qingming Huang, chief engineer on the improved GSA. Since he wasn’t hung up on the Lunar New Year or other parts of Chinese culture, he was easy to date, but he reminded me too much of Hefei Ye, so I distanced myself, unable to deepen the relationship.

When we landed, my subjective age was thirty-seven. By the Western calendar, which didn’t mean much at that point, I was forty-eight. Either way, I would never return to the Earthsphere.

I started spending more time at the lab in pursuit of the piecemeal Uluru updates.

The objects moving with the seasonal changes had been found to be bubbles of fat that couldn’t quite be called life just yet. Still, we knew the bubbles moved seasonally in groups of like chemical makeup, to places where it was easier to maintain surface tension. Though it was unclear if they had metabolisms, much less intelligence, I was excited to see them traveling together, but the survey had ended there.

The survey on the ground to ascertain what was inside the bubbles was entrusted to a team of five that I would lead.

Having agreed to gene therapy for methane respiration, I and my team members, who were also immigrating to study the life forms, analyzed what little data there was. We could hardly wait to land on Uluru. By the time Tau came into view, sparkling pink, in January of 2133, we had resolved to set foot on the planet.

That was when it happened—unexpected news arrived.

“Chunyun Special Flight?”

I repeated what the team member who brought the report said.

“Where is it planning on returning to?” another confused team member asked.

“China, apparently.”

“Even if they hurried using the latest black hole fall drive, it would take thirteen years. Even light takes eleven years and eleven months.”

“Yeah, I know. But they told anyone who wants to go to gather at the GSA tower—the central lobby. All the kakyō are there.”

“...Seriously?”

When I took my staff and went to have a look, there was an apparatus we’d never seen before in the back of the lobby.

The easiest way to explain it would be a dome that ten people could fit under. It was attached to a graviton track branched off from the accelerator.

There were kakyō working around the dome. Surprisingly, their leader was my partner up until recently, Qingming Huang.

Once the ring of people watching them work had grown two and then three thick, Qingming Huang stopped working, projected himself via augmented reality, and began to speak.

“Everyone, I’m sorry to have kept this quiet until now. We Chinese immigrants brought gravitons entangled with the Earthsphere on this trip.”

Confusion spread throughout the immigrants who were listening to his explanation.

Everyone knew that the states of twin-like particles would be the same at the same time across space—that’s quantum teleportation—but we didn’t understand what it had to do with the Chunyun Special Flight.

Faced with the murmuring crowd, Qingming Huang scratched his head self-consciously. “We were entrusted with these particles thirteen years ago, but even we don’t know what will happen as a result of this experiment. After all, our knowledge on the matter stops thirteen years ago.”

A voice rose from the gallery. “Experiment? You’re using the GSA?”

“Yes, we were told to put fifty trillion entangled gravitons into the accelerator and observe them in this dome. We have no idea how much progress our friends in the Earthsphere have made in the past thirteen years. It might be that the gravitons simply evaporate, but...”

I spoke up. “It doesn’t matter what happens if it doesn’t work. What are you trying to accomplish?”

Qingming Huang looked at me.

“Hefei Ye is on the other side.”

When my eyes widened, Qingming Huang told me the experiment was already starting and turned to face the dome.

The kakyō stopped what they were doing and stood up.

Light began to gather at the center of the dome.

“It’s a wormhole,” Huang Quingming said. “Using the interference of the gravitons positioned in the same location in the Earthsphere, we’ve created a wormhole. We opened a hole in space.”

When the light faded, a different space was visible inside the dome.

Hefei Ye was there.

I was about to leap for him, but Qingming Huang spread his arms and barred my way.

“Sorry, we go first.”

“Let me through!”

“We’ve been waiting for thirteen years to celebrate Lunar New Year. Okay, everyone, let’s go home.”

The kakyō passed through the hole in space.

After they had all gone in, Hefei Ye walked out from the other side and wrapped his arms around me.

He seemed slightly older than he should have been from memory, but my body remembered his strong hugs. My tears overflowed.

“I made it,” he whispered.

“Huh?”

“I caught you before you could stop being human. I could keep us from becoming another species. Now we can go anywhere in space and still return.”

“Oh, oh yeah.”

Before the emotions rising in me rendered my speech mere sounds, he whispered, softly, something so kind: “Just like migratory birds.”